The Sun

You shouldn't stare directly at the sun.

Everybody knows that.

But on this beautiful Norwegian May afternoon I simply can't help myself.

Transfixed, my retinae lock on to the glowing orb.

Blinded by its radiant corona.

Blinded, not by the ultraviolet radiation of our life-giving G-type main-sequence star, but by the brilliant flash of sunlight emanating from the Munchmuseet's 6th floor Monumental exhibit.

The Sun, a painting by Oslo's native son Edvard Munch, is a work that is indescribably expansive. indescribably vibrant. indescribably expressive. indescribably affecting. So indescribably indescribable that I am struggling to, well, describe it.

Stretching a staggering 26 feet across and 15 feet high, the marvelous painting irradiates bright, beautiful sunshine from its sprawling canvas. "I saw the sun rise up above the rocks - I painted the sun," Munch once pithily described his inspiration for the painting; a statement so modest it borders on arrogance.

Standing beneath the painting I feel its warmth, I feel its resplendent rays wash over me. I find myself contemplating, is the sun is rising? Or is it setting? Are we witnessing the aspirational glow of boundless potential? Or the last glimmers of a brilliant memory?

Just as the earth rotates around the sun, that eternal galactic constant, so too do our lives rotate around The Sun. We crawl, we tumble. We walk, we stumble. We make friends, we lose touch. We fall in love, we mend a broken heart. We get married, we have kids, we travel across oceans, we grow old. All the while The Sun's rays remain statically frozen in time, our lives revolving around its magical glow. It's neither a rising nor setting sun; it's our journey through the human experience that rises and sets around the painting.

This prodigious work isn't even his most massive. The Researchers, a painting of children digging and exploring in the sand, measures an astounding 16' x 36'. That's nearly the size of a pickleball court.

The feeling is surreal standing beside these remarkable works of art, if not for the artistry of it all but the logistics of creating these monstrosities, let alone transporting and hanging them.

Speaking of...

Norsk Teknisk

Norsk Teknisk, i.e. the Norwegian Museum of Science and Technology, sits a quarter mile from the source of the Akerselva River; steps from where Lake Maridalsvannet releases her stored precipitation to begin its journey to the Osloflord. I've decided to spend my final day in Oslo here because, I mean, have you met me? Also the Viking Ship Museum is closed until 2025.

Norsk Teknisk wastes no time showcasing the importance of the Akerselva with a 20' replica water wheel spinning inside the main atrium.

The museum's collection features scientific and historical artifacts that paved the way for Norway's ascension to a modern industrial society. And in one case, literally paved the way as the museum features the world's oldest surviving steamroller, dating to 1878, 30 years before the advent of Ford's Model T.

To my utmost chagrin I am constrained for time today, as my ferry to Copenhagen sets sail at 3 PM sharp. By necessity I'll have to blow through this institution at a pace that will not allow me to fully appreciate the science and the technology. Alas.

In my whirlwind tour I find rooms dedicated to

A coin-operated phonograph that is the predecessor to today's jukeboxes.

An historical assortment of bicycles;

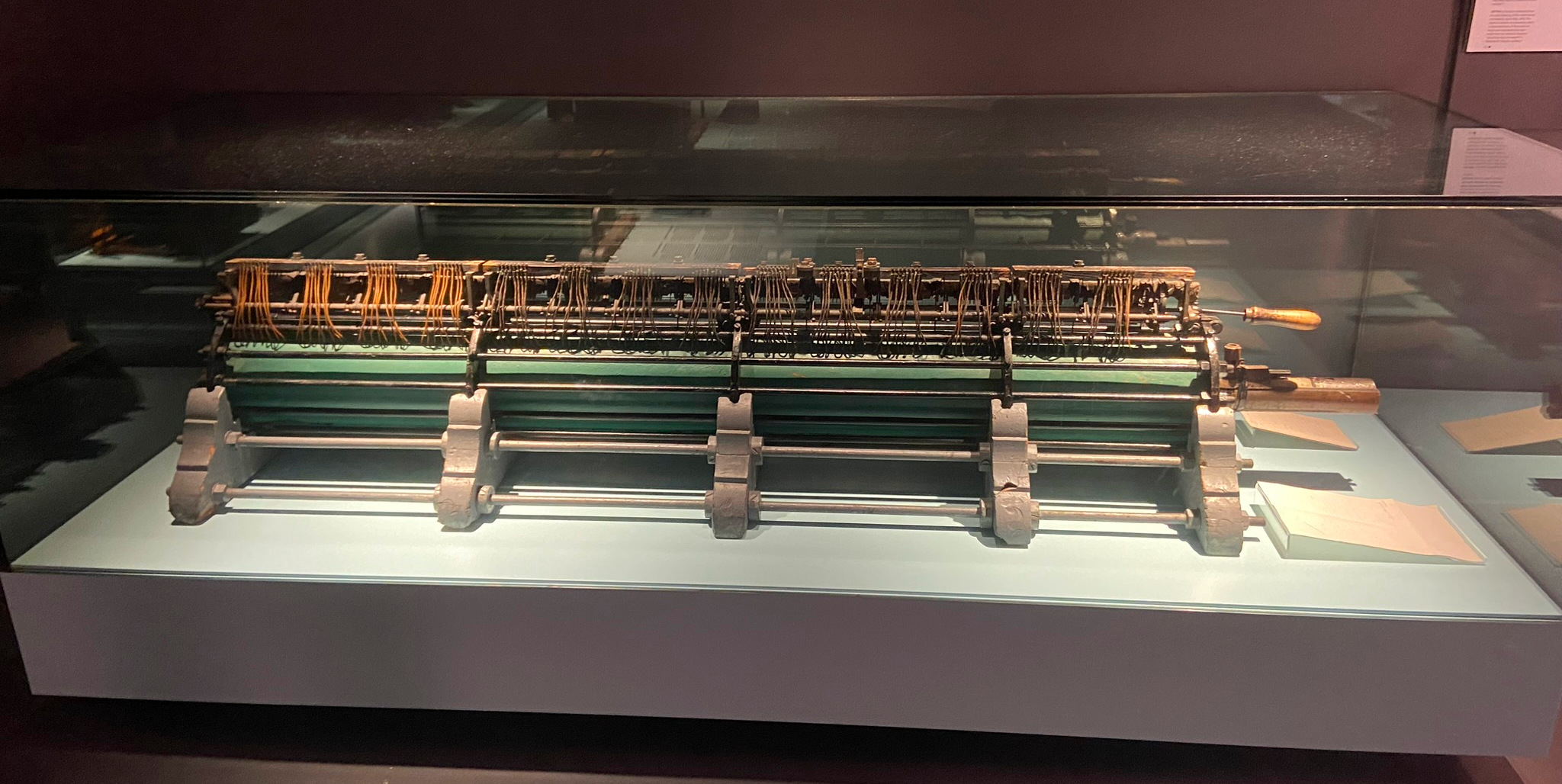

The innards of a warship's steam turbine used to power the ship.

An early capacitor used to conduct trailblazing electrical experiments;

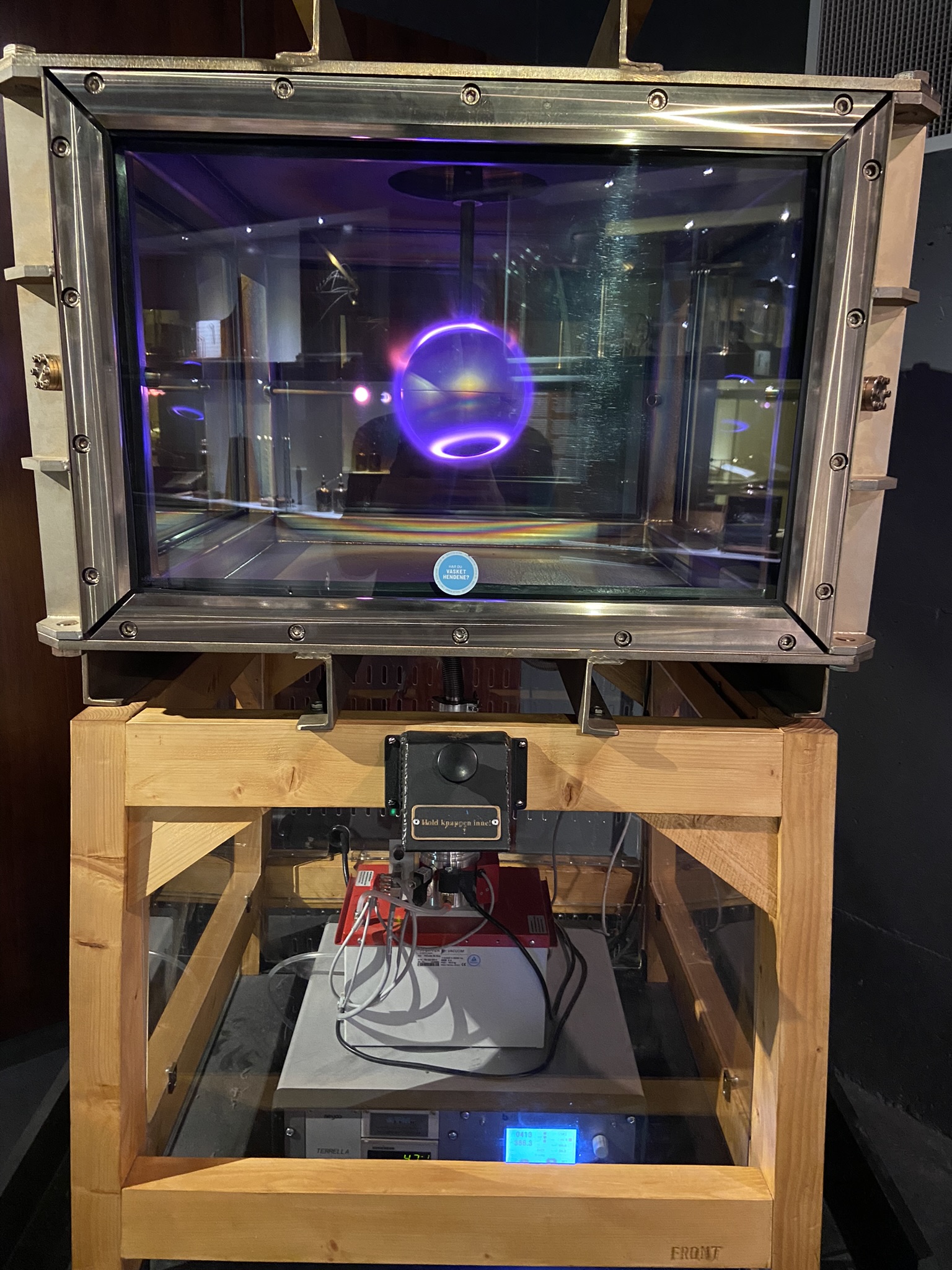

A magnetized ball (terrella) glowing in a chamber with the same phenomenon that brings us the Northern Lights.

In 1764 Danish historian Peder Frederik Suhm, reflecting on Norway's place in the scientific landscape of the era, remarked, "no country in Europe was in worse circumstance for scientific growth and progress." This despite a leader of European scientific discovery sitting just a short jaunt to the south in Copenhagen, most notably at the Royal Society of Sciences of Copenhagen.

In an effort to bolster Norway's scientific stature King Frederik V established The Free Mathematical School in Oslo, and the Royal Norwegian Mining Seminar in Kongsberg in the mid 18th Century.

This telescope was built by Abraham Pihl, a Norwegian vicar who had assisted Thomas Buffe at the observatory in Copenhagen. It features an achromatic lens, a revolutionary technological advance for the time that reduced the blurriness that was common in telescope lenses of the day that suffered from chromatic & spherical aberration.

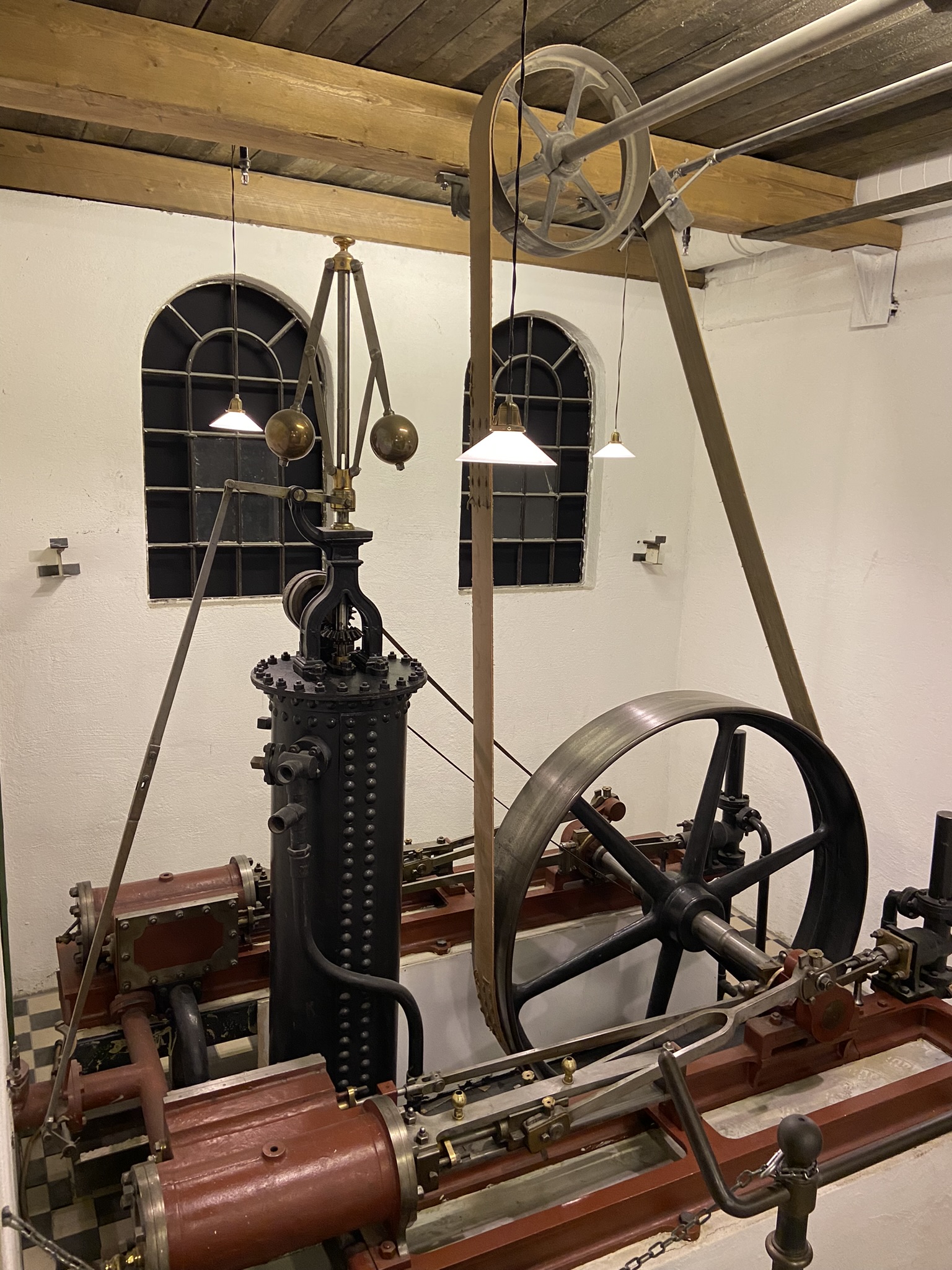

This steam engine was used to power dozens of machines at a factory using a purely mechanical linkage. The steam engine would spin the large wheel, turning a belt to power the smaller wheel overhead. This wheel was connected to a shaft that ran along the ceiling of the workshop.

This shaft was fitted with numerous drive wheels, which were connected via belts to drive shafts on either side of the workshop, which were in turn connected to each machine.

This seems atavistic by today's standards but at the time it was state of the art. From an engineering perspective it's fascinating to see each component of a mechanical system laid bare. From a human perspective it's hard not to imagine the interminable hours of excruciating work performed here; how many digits, limbs, scalps caught in the drive belts - people caught in the literal gears of society, an unseen cost of progress.

The Oslo Waterfront

Prior to the Fjord City urban renewal project in the mid-aughts, the Oslo waterfront was an industrial snarl, clogged with maritime shipping infrastructure, train yards, and the 8 lanes of European Route E-18. As part of the Fjord City project, the port was moved to Sørhavna, the train yard was relocated, and the highway was re-routed to a tunnel under the harbor.

These infrastructure improvements opened the waterfront, affording the citizens of Oslo acres of prime fjordfront real estate to bask in their Scandinavian happiness. The waterfront development is anchored by the Oslo Opera House, home to the Norwegian National Opera and Ballet, and the Oslo Public Library, home to.... a lot of books. 450,000 of them in fact.

One day, on a stroll along the waterfront, I pop into the library to try to read them all in one go.

Opening at a banner time for public gathering - June 2020 - the Deichman Bjørvika Oslo Public Library embodies the philosophy and aesthetic of the Oslo waterfront. On the design of the library, the architects remarked, "we think we have succeeded in making a building that is huge, but at the same time feels intimate so people can feel they belong there." Further, "here you will find spaces for meeting, rehearsal rooms, gaming rooms, exhibition niches, a record studio, silent reading rooms etc. Even though the books still have a strong presence this library is designed first and foremost as a place for people."

With their design, the architects hoped to not simply bring people together, but to bring them together while inviting the outside in. The building's façade is wrapped with windows and the roof boasts three diagonal light shafts that allow for sunlight to spill from the roof all the way to the ground floor.

The most striking feature of the building, however, is the fifth-floor cantilever. Jutting 60 feet towards the fjord, the top floor of the library boasts a bright amphitheater with gradual steps down to the fourth floor. The overhang serves multiple purposes, allowing breathtaking views of the Oslofjord, while preserving street-level views of the Opera House.

While I was not blessed with the opportunity to grace the halls of the Opera House I did walk on top of it. Opened in 2008, the Oslo Opera House finds itself in the small minority of structures where the general public is encouraged to walk on the roof. The winner of an open competition besting 350 other entrants, the Opera House's exterior of white granite and Italian carrara marble give the impression of an iceberg slinking away into the frigid waters of the fjord. The building's sloped roof invites all who arrive to walk upon her back, to mount the humble structure, a gesture offering stunning views of the fjord and city

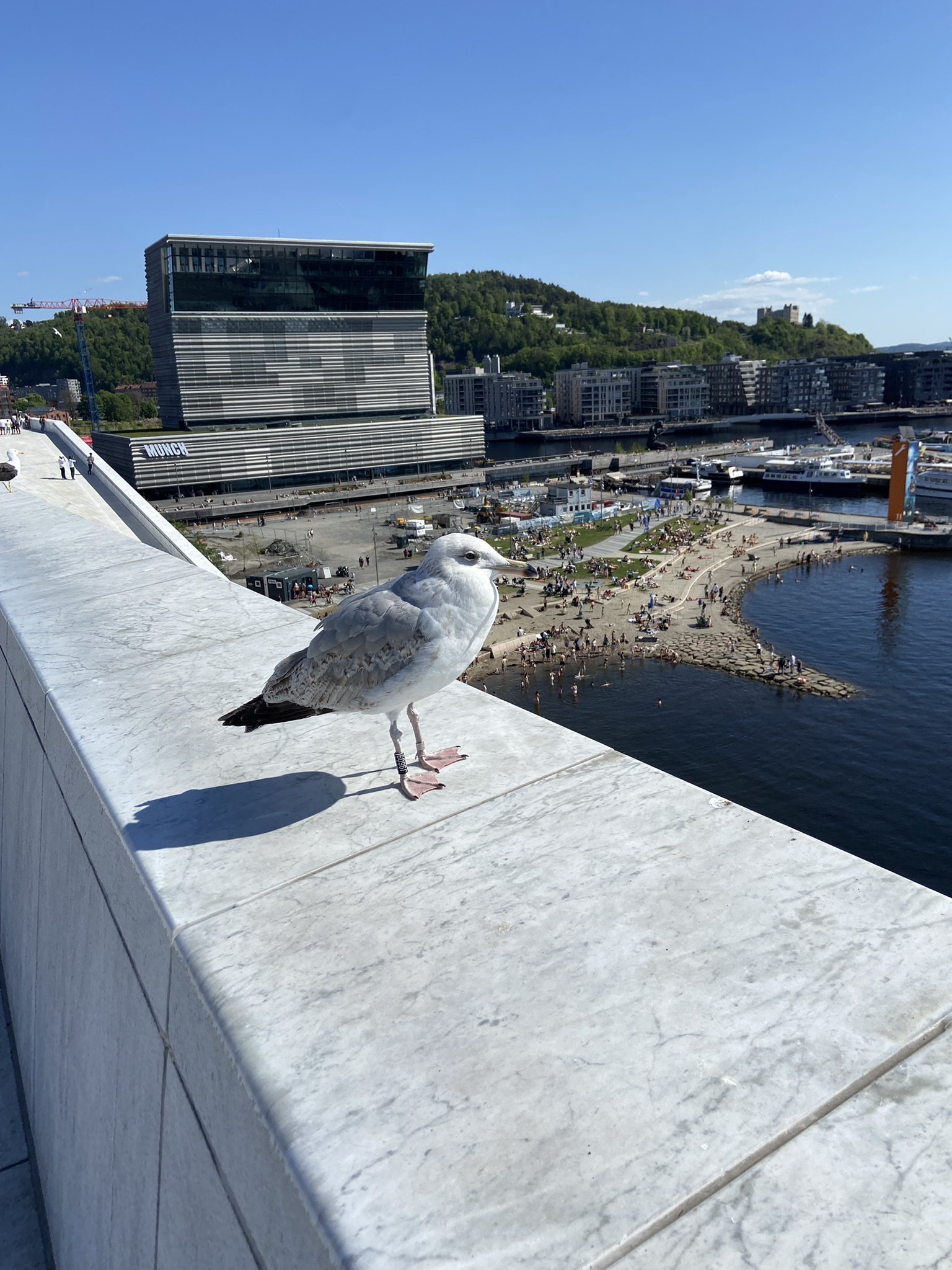

The southerly view offers a glimpse into the joys of summertime Oslo - a throng of epicureans in swimming costumes frolic and bask in the beautiful weather on a beach fronting the Munch museum.

Just then a surly gull perches on the marble banister an arms-length away. This bird, who I'll call Gustav, is perhaps another voice in the crowd offering a take on the architecture of the Munch museum.

Munch

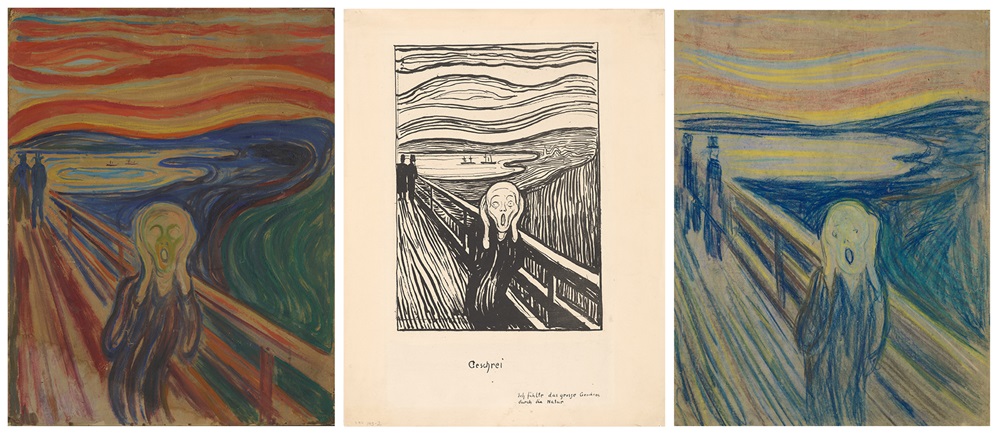

The Edvard Munch Museum (stylized Munch) commands an inviting or ominous presence on the shores of the Oslofjord depending on who you ask. It's easily the most disputatious edifice gracing the Oslo skyline. The angular, 13-story "vertical museum" seems to bow towards the fjord, as old man with his hands clasped behind his back talking to squirrels in the park.

The (few) proponents of the structure point to its distinctive architecture, sustainability bona-fides, and respectful, bow-like posture towards the Oslo city center, Opera House, & Oslofjord. Opponents claim it's harsh, orthogonal lines mar an otherwise elegant skyline. Still others contend that the museum blocks the view of the fjord to some of the lower economic neighborhoods in the shadow of the monolith.

It's nothing if not controversial.

The author of the above take, architect Gaute Brochmann, editor of the journal Architecture N, further clarifies in the article, (as translated by my internet browser)

But what the Munchmuseet lacks in architectural charm it abounds with spectacular works of art.

With installations spanning 6 of the museum's 13 floors (the others are used for performances, administrative tasks, and a restaurant/bar) visitors can spend a day at the museum and still not see all there is to see within its capacious 500,000 square feet.

As we wind through the halls of the museum I'm enthralled by the third floor's The Shape of Freedom exhibit. Norway's largest exhibition of abstract expressionism, or art informel as the Euros call it, tells a story of a world recovering from war. These are the kinds of works that I'd have the natural tendency to deride as "throwing paint at a wall" or "something a trained simian could do, and it wouldn't even have to be trained that well."

But the museum does a masterful job of telling a story through their collection. As you enter the exhibit you are welcomed by a series of pieces that portend the storm clouds of war gathering over Europe in the 1930s.

As you continue through the space the pieces slowly shift from an ominous sense of impending doom to doom incarnate. Photographs of tattered studios in war torn cities accompany works dominated by dark colors and harsh lines. Dispersed between the pieces are are descriptions of the milieu in which the artists lived and worked. Art is always an expression of its time but I have to imagine wartime only emphasizes the degree to which art reflects the world it inhabits.

By end of the exhibit the mood of the pieces begin to gradually lighten, reflective of a world emerging from the largest bloodletting in history, hopeful for what lies ahead, thankful for surviving the carnage, and rueful for having to live through a catastrophe completely out of their control.

The rest of the lower floors present a handful of other exhibits with titles such as Lost in Color and Painting the Unspeakable that highlight works from Scandinavian artists and a smattering of others from around the world. Each installation tells a story, each installation complements the works of Edvard Munch to be seen shortly in the floors above.

Edvard Munch

Norway's most celebrated artist, Edvard Munch was born in a farmhouse in the small pastoral town of Løten in 1863. Around his first birthday his father was appointed medical officer at Akershus Fortress, then the Norwegian royal palace, and moved the family 80 miles south to the city of Christiania.

Christiania was a city constructed from whole cloth by King Christian IV of Denmark in 1624. After a fire destroyed the existing city, Ol King Chris decided to rebuild across the river and, of course, named it after himself. In 1877 the name was changed to Kristiania, which lasted until 1 January 1925 when it was again renamed to... Oslo. The fact that their capital city was named after a Dane just didn't sit right with the Norwegians.

As a child Munch often fell ill during the winters and was held out of school, where he began to draw to keep himself occupied. Munch's mother died of tuberculosis when he was just 5 years old, leaving his father Christian to raise Edvard and his siblings alone. Despite his father's generally positive and supportive parenting his overly pious demeanor had an effect on Edvard, "My father was temperamentally nervous and obsessively religious—to the point of psychoneurosis. From him I inherited the seeds of madness. The angels of fear, sorrow, and death stood by my side since the day I was born."

This overbearing influence, combined with his mother's death and a hypochondrical comportment, contributed to his distinctive macabre style.

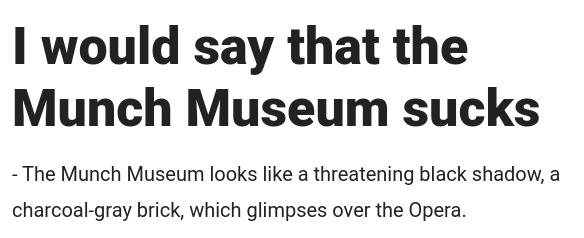

All this is to say if you don't know who Edvard Munch is, he's the guy who painted The Scream.

You know The Scream

So yeah, I didn't know who Edvard Munch was until I had already been in Oslo a few days, "have you gone to the Munch museum yet?"

"Not yet, but it's on my schedule!" I confidently replied without a clue what they were talking about. Later, when cloistered in the safety of my own uncultured ignorance, I looked up this Munch fella.

Ohhhhh THAT guy!

I have a vague recollection of a dreadful attempt at recreating The Scream in elementary school art class, but likely due to my incredibly untroubled and stress free upbringing I just couldn't access that pain behind those eyes.

The inspiration for the piece was a sunset walk along the Oslofjord,

One evening I was walking along a path, the city was on one side and the fjord below. I felt tired and ill. I stopped and looked out over the fjord – the sun was setting, and the clouds turning blood red. I sensed a scream passing through nature; it seemed to me that I heard the scream. I painted this picture, painted the clouds as actual blood. The color shrieked. This became The Scream.

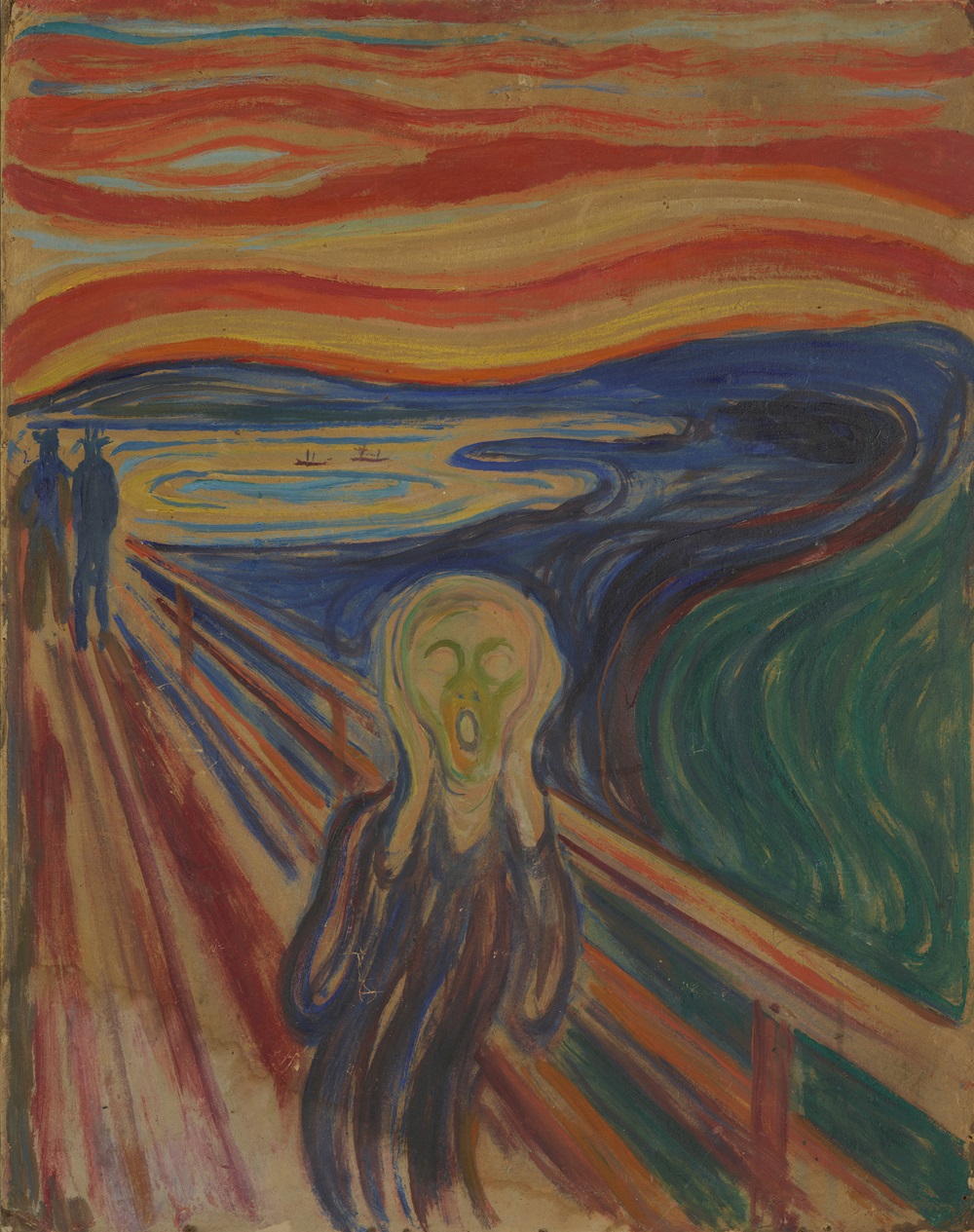

The painting is actually one of a series of works - two paintings with tempera and oil, two drawings with pastel and crayon, and a few dozen prints from a lithograph. The museum retains 8 versions of The Scream - one painting, one drawing, and 6 lithograph prints.

As we ride the escalator to the 4th floor we leave the non-Munch section of the museum and enter the Munch exclusive floors. And since they maintain nearly 27,000 pieces of art by Munch we will not be wanting for art on the next 5 floors.

Munchmuseet, fully ascribing to the give-the-people-what-they-want philosophy of design, immediately satiate the visitor's thirst for Skrik, as The Scream is called in Norwegian. The exhibit consists of a dimly lit three-sided alcove featuring a different version of Skrik on each wall. Since Munch created each version on paper or cardboard they are more fragile than works on canvas. As a result they only display one version at a time on a rotating schedule, while "the two others rest in darkness" as the museum melodramatically describes.

The version on display during our visit is a black & white lithograph. While the museum says that "all the versions are different, but equally powerful" I have to day that I think the colored painting is probably more powerful. But then again I have absolutely no idea what the hell I'm talking about.

The rest of the 4th floor is filled with Munch's explorations of humanity, filled with sections such as Oneself, Gender, In Motion, Love, Others, Alone, Outdoors, To Die.

And a painting of a bartender who looks like Bill Murray.

I'm dancing perilously close to the cliffs of my artistic scholarship, so I better quit now. All I have to say is the Munchmuseet is well worth a visit, despite the harshest critics' opinions of the exterior.

Hell even the the floors are beautiful.

Unfortunately the rooftop cafe is closed by the time we summit the charcoal-gray brick, but we do make a stop in the Chamber of Chaos - a "fantastical, imaginative play-space for children, where normal museum rules do not apply."

So we spend a few minutes breaking normal museum rules because who doesn't want to act like a kid every once in a while?