Five

Six

Seven

Eight

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

1

2

3

skip

5

6

7

8

1

2

3

skip

5

6

7

8

1

2

skip

skip

skip (shit!)

6

7

8

Welp, it only took till my 3rd pass for my first blunder. That set of three skips you see up there in red? That should have been another single skip - the triple skips don't come until the next lap. Well, shouldn't come until the next lap if we're being pedantic. I know I was bound to mess something up, just didn't think it would happen so quickly. We'll just say I got it out of the way early.

Behind the curtain after the pass I look at Cate,

"Ugh I accidentally started the 3-skips a lap early. Whoops!"

"OMG I did too!"

"Ha! Seriously?"

"Yeah, I think we're just a little excited for our first performance. It happens."

Seeing as we were in the middle of the line when we committed our faux pas it very well could have looked intentional. At least that's what we tell ourselves as we prepare for our next pass. No time to dwell on the past.

Bottom photo: skipping when skipping should be skippy'd

It's Art, Get It?

On the spectrum of human pursuits artistic expression is unique in its subjectivity. There's no one way, no right way, no wrong way to create, consume, or appreciate art. And that's where it derives its beauty. Y'know, the eye of the beholder and whatnot.

In terms of subjectivity Mark Haim's This Land Is Your Land is an extreme exercise on the matter. The piece is so unfailingly unique that no two audience members will walk out of the Nasher with the same perspective. And each perspective is perfectly valid.

Even the stage is set up to encourage novel experiences. Arranged in a configuration that (I just learned) is known as a "thrust stage," the audience surrounds us on three sides. Personally, I'd call it the "Easy Company" but Mark calls it an interactive viewing experience. Audience members who are seated directly facing the stage are treated to a completely different show than those on the flanks. So even the same person watching the same show from two different seats may interpret it differently.

During my first viewing of the Paris recording I was floored by a connection between Woody Guthrie's This Land Is Your Land and what I considered to be the most powerful section of Mark's. When I asked Mark about this connection he hadn't considered it when creating the piece. It's just a coincidence amplified by my Oklahoman-ness. Each audience member will surely make a connection that feels just as profound to them as my Woody Guthrie connection does to me.

After the show, audience members commented on the sense of isolation in the piece; the lack of connection between the six dancers on stage, each weaving their own way through the world. Then, just minutes later, others remarked on the feeling of community shared between the dancers.

It's individualistic. But it's also community. A dance. But also not a dance. A statement. But not a statement.

In Mark's own words,

"It's based on a very simple pattern that keeps mutating for 14 performers that also involves about 200 Starbucks cups, 14 rifles, 14 pistols, 15 cell phones, 17 beer cans, and a whole bunch of costumes set to a whole bunch of country music."

It's an artistic expression that can be viewed and interpreted an infinite number of ways. Byron Woods, the theater & dance critic for INDY Week, a Durham-based independent newspaper, opined in his review, "flashy movers on a serpentine catwalk execute a slow pan across a landscape of mindless consumerism." It certainly exposes some of the most salient aspects of our culture, but the most wonderful part is the fact that there's no message. There's no agenda. It's simply Mark presenting the world the way he sees it and allowing the audience to come to their own conclusions.

At least that's my conclusion.

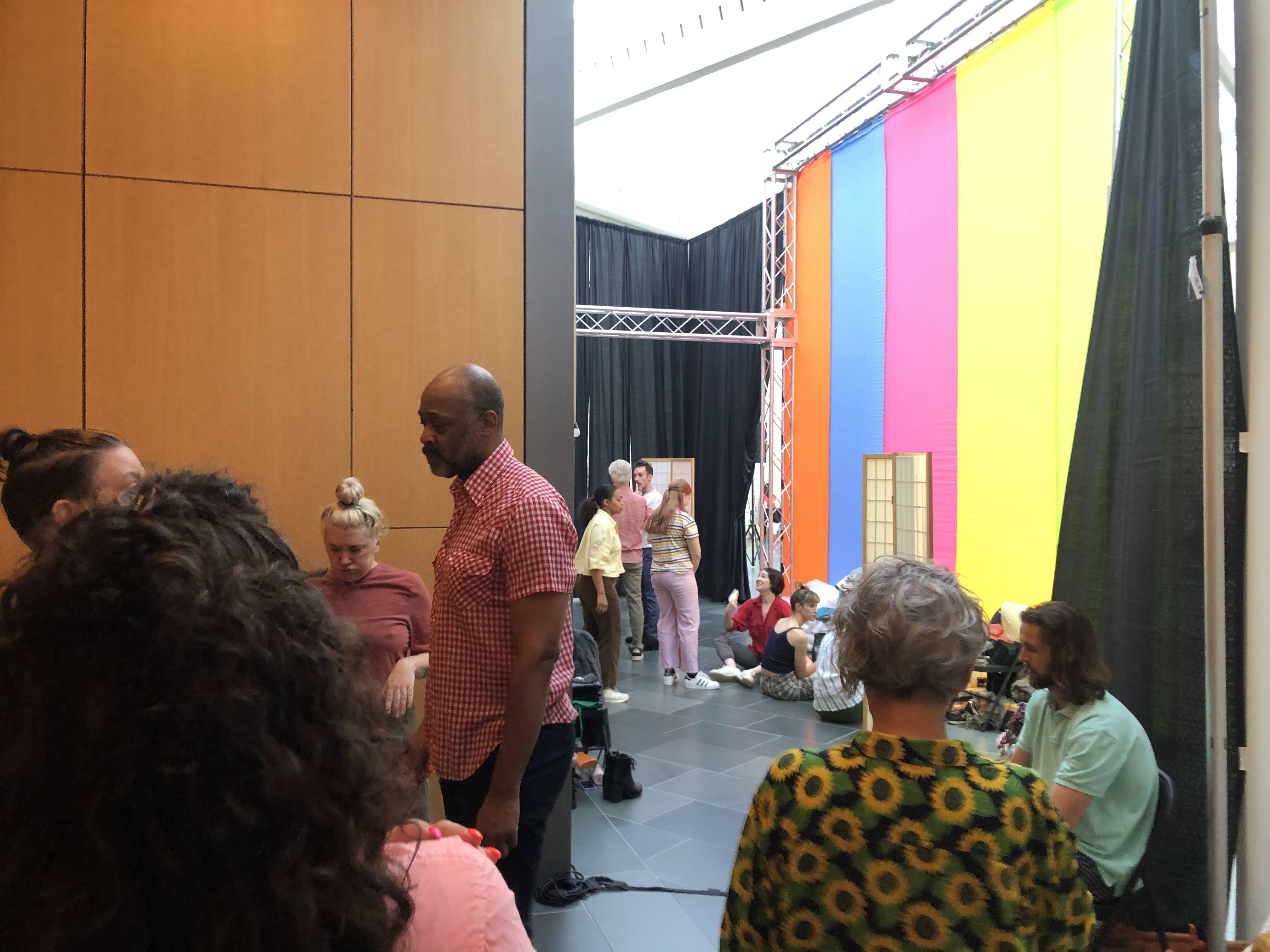

Dress Rehearsal

The day before opening night we mosey over to the Nasher for a full dress rehearsal in the interactive viewing experience. When I stroll into the museum's capacious atrium my jaw drops to the floor. Vaulted 45 feet overhead a stunning web of glass and steel envelops the 13,000 square foot Great Hall. The ferrosilicate structure is conjointly supported by 5 immense beams, none of which span the room's full breadth. It's somewhat like that classic dad trick of folding the flaps of a cardboard box to stay shut without tape. It's a beautiful piece of engineering.

In the words of Rafael Viñoly, the Uruguayan-born architect,

A collection of five separate, rectangular volumes arranged in a loose radial pattern near the top of a gentle slope define an irregular, pentagonal central courtyard topped by a glass roof. The complex, almost vertiginous geometries of the atrium roof are formed by a hierarchy of structural systems, all supported on five primary beams.

This seemingly simple network of structural supports adds rhythm, lightness, scale, and openness to the column-free public lobby and event space at the heart of the museum and also incorporates the building’s mechanical systems.

It's a magical venue. It's also my first introduction to the bewildering experience of rehearsing in a new space. During our first dress at the Nasher I make mistakes I haven't made in over a week. I can't keep my count. I can't remember my choreography. I'm fully discombobulated. It certainly doesn't help that the green slate floor tiles are slanted at an angle oblique to our walking path.

After the run-through I ask my fellow performers if they had similar struggles and they confirm as much.

"Every time you rehearse at a new place that will happen. You'll be alright, that's why we did this."

Phew.

For our second dress rehearsal we are graced with an audience. Members of the ADF staff who have schedule conflicts fill the Great Hall for our last run-through before the big day. Much the same as the venue adds a new layer to the performance, a live audience significantly changes the dynamic. I'm grateful that we are able to rehearse here and with an audience. As an engineer I'm always on the lookout to isolate as many variables as possible.

Then right before the first performance Mark adds another variable.

"Andy, I know we haven't practiced this but I want you to grab the spear from Cate and carry it offstage."

Sure thing, Mark, let's just throw a last minute curveball to the dancer who'd be more comfortable hitting a literal curveball.

"Yeah, no problem," I say with a false confidence that hopefully belies the fact that it's at the very least a small problem.

So I practice the spear handoff a few times with Cate, a move that requires a pirouette opposite of our normal direction. And of course a last minute scribble on my spreadsheet.

Let's Get On With It

Outside of the 11th hour spearouette addition I feel ready. Rehearsals have worn me down and I'm ready for the real thing. I've got my system down. I'm prepared. Calm. Confident.

That night I sleep like a damn baby. When I arise I find a ladybug on my pillow - that's gotta be good luck right? But then again, maybe I don't want good luck? I'm not really sure what to make of dancer superstitions.

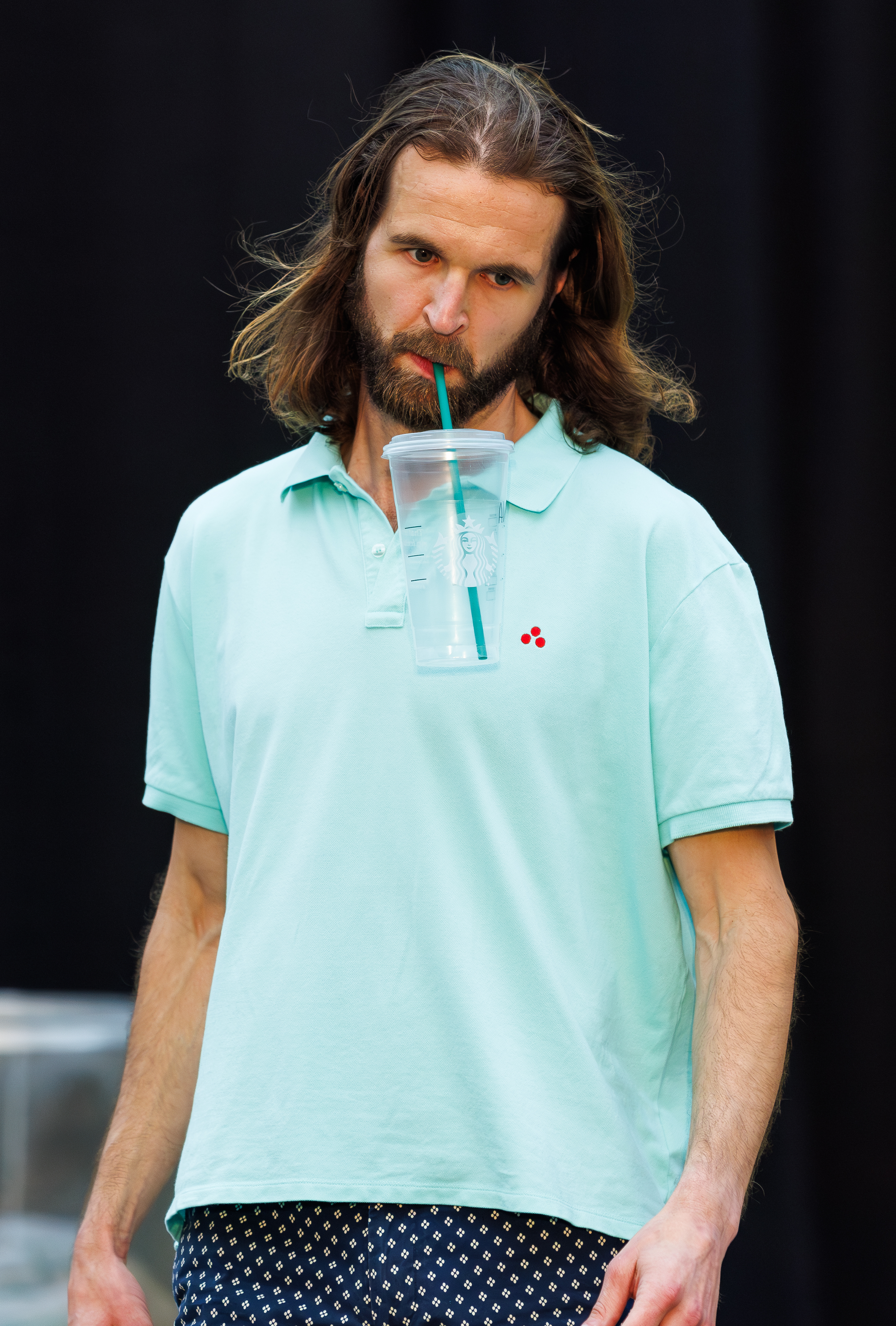

I arrive to the Nasher a few hours ahead of our 6:30 PM show. Around 4:30 we do a tech rehearsal, which I learn is just a breezy run-through with the music but no costumes or props. Like a Thursday football practice with no pads.

The time between tech & the performance is filled with much milling about and nonsensical banter. I'm confident but still stress eat about half of the potluck snacks. Thomas Earl Petty was right about The Waiting. Our heroic stage manager, Gabby, has the unenviable job of appeasing contingents from the Nasher, ADF, and the security detail, all while wrangling a group of nervy performers.

15 minutes before showtime Gabby leads us from the green room backstage. We chat idly, review notes, stretch out, waiting anxiously just to get the show on the road. 6:30 comes and goes.

Dana reassures me, "these things never start on time, I'm sure there are still people shuffling in"

A few minutes later Gabby comes backstage and patiently tells us we'll be starting in 5. And in 5 minutes I'm greeted, once again, by that familiar contralto,

I take a load off and watch the organized chaos unfold around me. For each of their early passes, Alexandra, Renay, Matt, Cate, Allie, Hendri, and McKelynn are forced to make a frantic backstage scramble. They have 12 counts to make it from one edge of the curtain to the other, lest they miss their next pass. The frenzied scurrying continues until Carrie joins the ranks, providing a much needed respite for the beleaguered troops.

Around 4 minutes in, during my favorite Pontoon DockRock ballad, I rise from my comfortable lounged position, grab a cup and step in line right behind Cate.

One - Two - Three - Four

And Cate is off.

Five - Six - Seven - Eight

I step up to my mark at the edge of the curtain.

One - Two - Three - Four

And on the 5 I take my first step onto the stage in my inaugural performance as a dancer...

Deep Blue Lake

For our passes with a "neutral" facial expression, i.e. no smiling, scowling, or sneering, Mark instructs us to imagine we're staring off into a deep blue lake. Which, on the face of it, sounds like nonsense. But for whatever reason we all know exactly what he means. It's so nonsense that it makes sense.

So during these passes my mind's eye is locked in on Crater Lake, the deepest lake in the United States filled with pristine Pacific Northwest precipitation.

Mark's vision for our deep-blue-lake-gaze was expressed in an interview before his first ADF performance of the piece at the Nasher 10 years ago, "the piece is so much about the performing non-performance. Everyone is trying to look as if they're not aware that people are looking at them even though all eyes are on them."

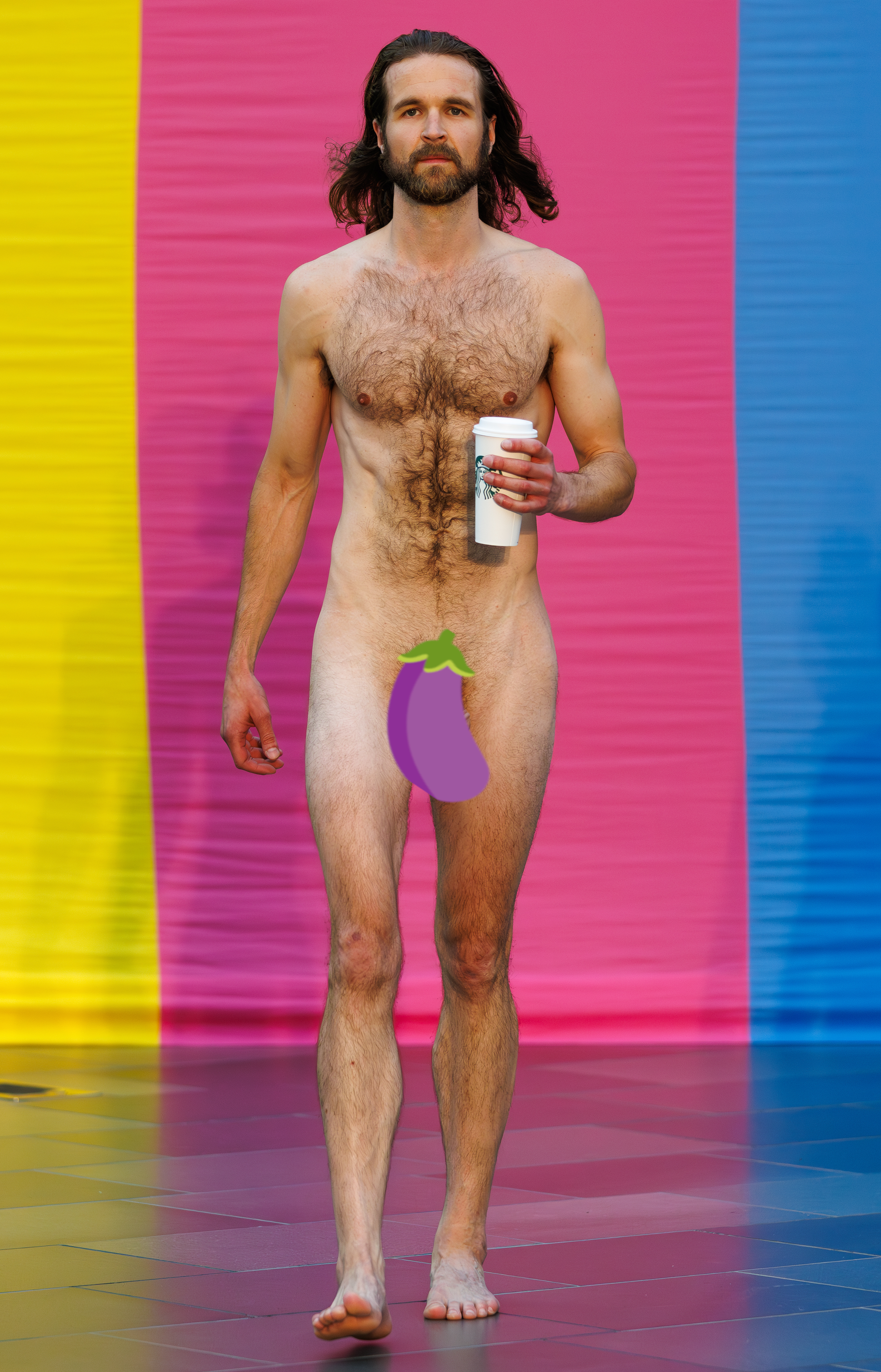

The most useful part of this for me stems from my inability to keep a straight face if I make eye contact with friends in the audience. During the first performance of day 2 I catch myself smothering a smirk during the nude section because I know my friends are in the crowd. As I stride out towards the audience I summon every ounce of concentration in my body to maintain a stoic stare; on the way back I have to ruthlessly crush the grassroots campaign of a grin organizing a jocund labor movement on my face.

During another section Mark provided his note for our facial expression thusly, "I want you to convince yourself you are the last line of defense in the war for Democracy, dammit!"

Photography by Ben McKeown, courtesy of the American Dance Festival.

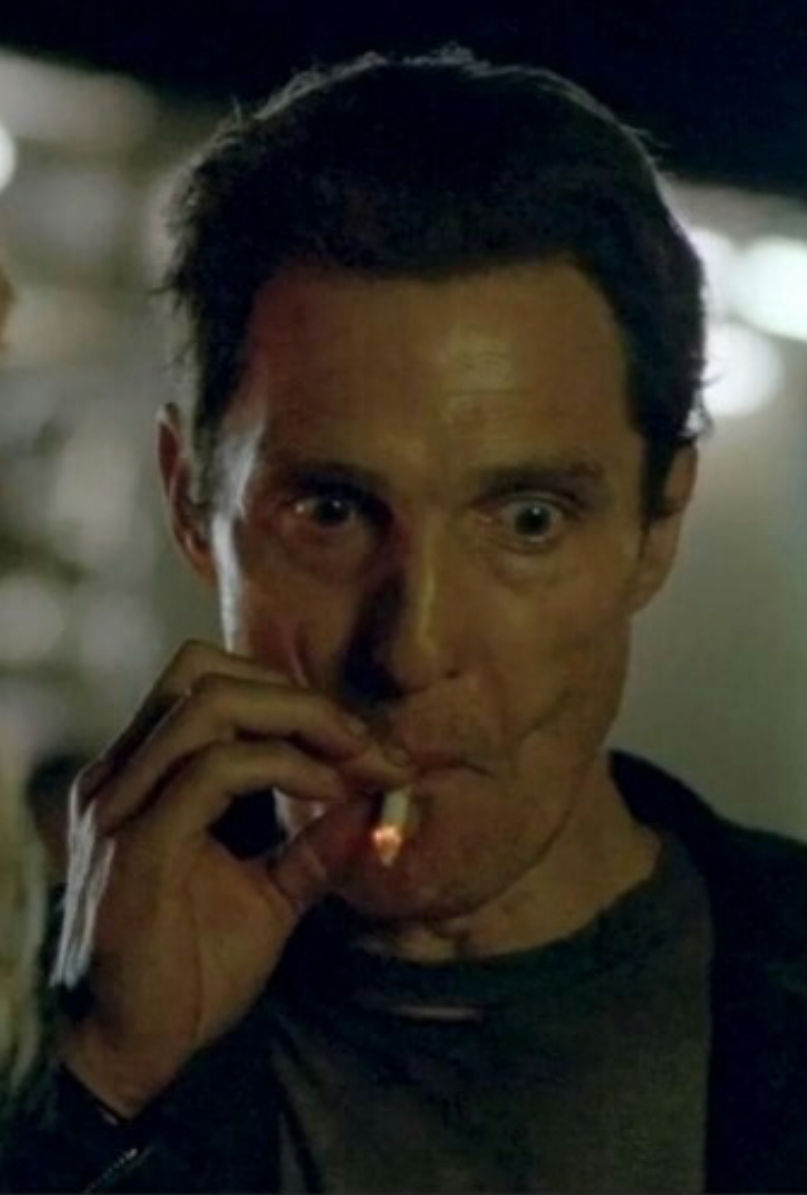

Then a few passes later, while we're carrying pistols Mark instructs us to wear a dead-eyed thousand yard stare. A catatonic numbness so deep we don't even realize we're carrying a pistol. It's a feeling that comes naturally to me - I was raised Catholic.

Photography by Ben McKeown, courtesy of the American Dance Festival.

Quick Change

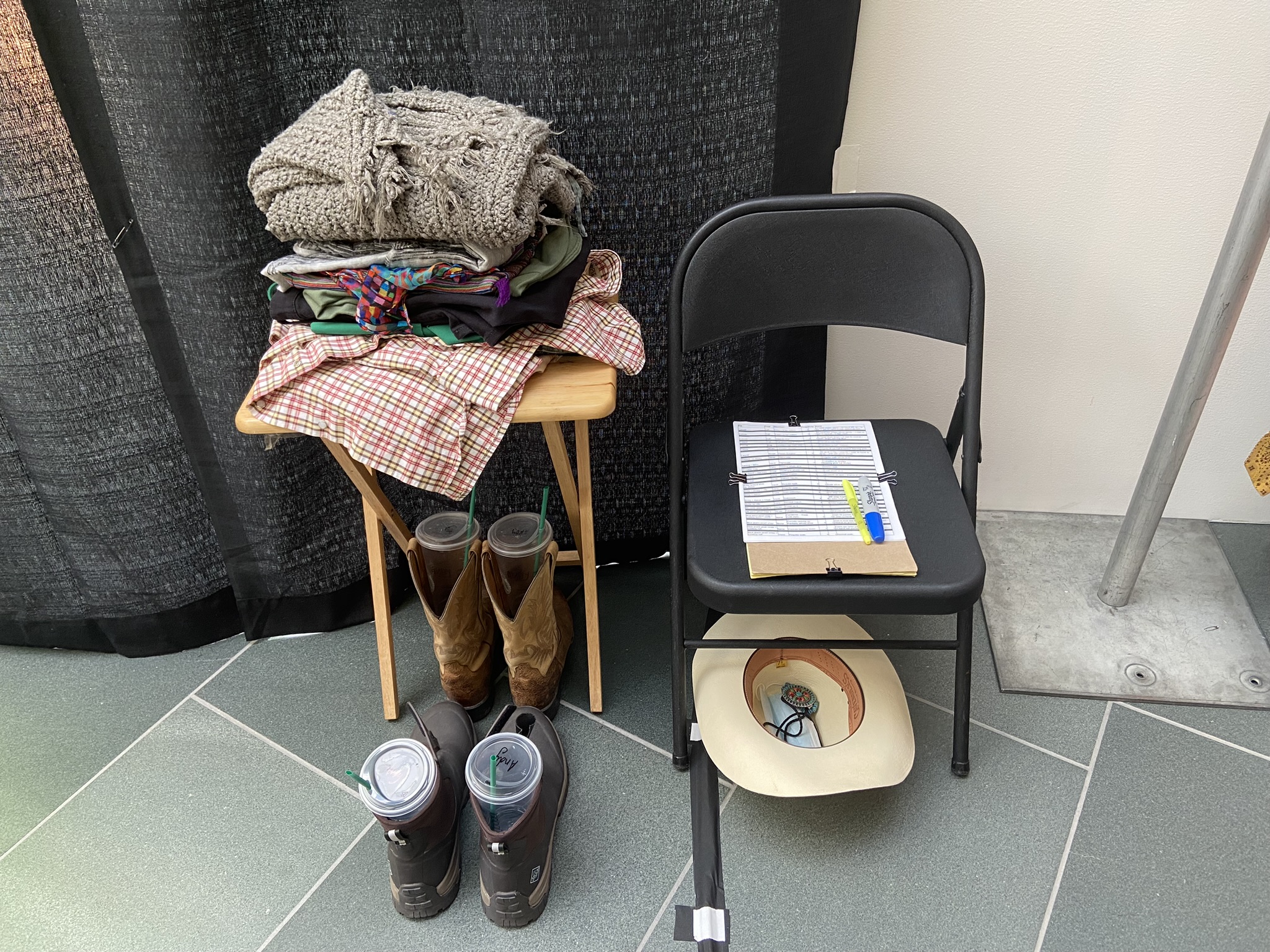

Throughout the course of the 1 hour piece I have 13 different looks. They don't all require a full outfit change; some are just an accessory here, new top there, different pair of jeans. But a substantial wardrobe to keep track of nonetheless. Before each performance I neatly stack each article of clothing in reverse order of their appearance.

And each costume change I frantically tear off my clothes & throw them into a pile. Entropy increasing with every pass.

Once we start the Shirleys our "high fashion" costume begins to take shape. We have 4 passes to metamorphose from our casual outfit to full high fashion, which in my case is our old friend Aspen down at the co-op. The first pass I put on my deep-V sweater. Second pass comes the sarong. Third pass is the purse. Fourth pass is the scuba headband, top knot, and colorful shawl lent by Gerri Houlihan herself.

If only the audience could take a peek behind the curtain. A sweaty maelstrom of flying blouses, jettisoned jeans, and the occasional mad dash to get in position just before your entrance. It took a few rehearsals to find out where we had a little buffer to take a breath and where we really needed to hustle. And which articles were the trickiest. For me it was my socks. With time I discovered that the secret was known by Rabbit from Twister all along: Roll The Maps (Socks).

For many others, tight fitting jeans proved to be their nemesis. During a particularly stuffy day in the studio Alyce proposed a remedy to the denim dilemma,

"If you coat the inside of your jeans with baby powder it helps get them on when you're sweaty!"

I take a moment to appreciate the simultaneous absurdity and sensibleness of the previous statement. I look at Alyce with a bemused smirk,

"If you would have told me on New Year's Eve that I'd hear 'if you coat the inside of your jeans with baby powder' this year I'd have thought 'well 2023 is gonna be a weird year.'"

Speaking of...

About That Whole Nudity Thing

I'll admit when I first saw the video of the Paris performance with full nudity I felt an initial jolt of anxiety mixed with excitement mixed with trepidation. The trepidation quickly gave way to a rolling cascade of immature mirthfulness. In short order, I dispatched a flurry of texts to my similarly puerile pals riddled with cosmopolitan aphorisms such as "hanging dong" and "cock out walk out." Hell we used to stage cock out rock out renditions of "Bohemian Rhapsody" in the high school football locker room after victories. My main preparation was a diet and workout program - because who would know about vainglorious pursuits more than a man who built an entire website to write about himself?

Photography by Ben McKeown, courtesy of the American Dance Festival.

But I don't want to breeze over the nudity because it's such an integral part to the piece's bold creativity. And my experience as a straight white male non-dancer is not representative of the rest of the company. As I listened to discussions of the nudity during rehearsal breaks I decided that I'd like to share a more diverse breadth of experiences than my own.

Spanning over 5 decades in age and a wide variety of backgrounds, the cast's journey to acceptance with the nudity was anything but uniform. While it was a completely novel experience for me, some of my co-performers had performed nude in the past. Most had attended performances with nudity. All understood that nudity is a form of artistic expression that has been around as long as dance has been around.

But how do you have that conversation with your partner? With your children? With your grandchildren? How do you draw the discussion from the realm of taboo to the realm of artistic expression? And why is nudity taboo to begin with?

⬤ ⬤ ⬤

In order to muster the courage to perform nude for an audience you must be comfortable in your own body. But that's just the start. The most significant mental hurdle is comfort with others seeing our bodies. Comfort with their gaze. Comfort with their judgement. Because each performer has their own relationship to their body and society's varying anatomical expectations based on age, gender, race, or sexual orientation, this was an easier road for some than others.

The performers who are active in the North Carolina dance scene (most of the cast) were further confronted with the anxiety of performing nude in front of colleagues, collaborators, community leaders, mentors, teachers, or students (an anxiety I avoided because I emphatically told my coworkers not to come). When I chatted with Dana about this aspect she relayed that it "was a question of making sure the people in my life and in my community who know me professionally, and outside of the dance sphere, were going to be ok with seeing me naked... Will they still respect me? Will they see me from now on in a work or other public event setting and imagine me naked?"

But when she brought it up with these same people nobody took issue with it. "It gave me the courage to be vulnerable and embrace my racing thoughts and fears as informative steps towards self-awareness rather than be paralyzed by them." Because through nudity we share "a trust that exists when we reveal ourselves whether physically or emotionally - and dance includes both."

One performer mentioned that her friends, when she told them about the nude section, all looked at her husband, what do you think about that? As if it was an act of infidelity. Because our society has so strongly linked nudity with sexuality it's hard to dissociate the two. Compared to some other, more more open-minded societies, it's rare we see nudity in a non-sexual setting. But there's nothing inherently sexual about nudity. And there's nothing inherently wrong about sexuality (which is another discussion altogether).

When Alyce first learned of the piece she felt a nervous apprehension, "it started out as a challenge, can I really do this?" Writing in her newsletter, she discussed her first screening of the Paris video, "there was an elegance of humanness in the vast range of bodies I observed on the screen. It was raw, real, it made my heart pound and my eyes were locked in." Upon reflection she felt compelled to say yes so she could "honor my body and what it's capable of and what it was been capable of creating for my career and for my life."

Once we began rehearsals Alyce found a serenity in the nude section, "I saw it as a moving meditation. During that moment I felt so connected with the group even though we never really came in contact with each other. That just became a peaceful moment." Again, from her newsletter, "I gave myself permission to be me, in my skin, in my body. I celebrated each moment and each movement. I felt loved and seen. I fell in love with myself and the cast."

But Alyce's proudest achievement has been teaching these valuable lessons to her daughter Amelia. "It was a powerful moment to share it with her. It was really special and I have reflected on that a lot, probably more than the actual performances. One of my values of being a mother has been to raise her without a lens of judgement, especially when it comes to our bodies because there's enough of that in the world." By confronting these complex experiences directly with Amelia, Alyce is providing the kind of emotionally mature guidance she is unlikely to get from her friends, school, or other elements of our society. It's what (I have to imagine) makes parenting such a challenging yet rewarding pursuit.

Other performers discussed the counterintuitive concept that the nude section actually felt the least intimate section of the piece. For Cate, an action as simple as smiling during our Shirley passes felt more intimate than the nudity. "During that section we're sharing a part of ourselves, whereas the nude section we're just bodies... it felt empowering because my body just existed, free from all our societal expectations." This realization helped her, along with a number of other performers, mentally prepare for the nudity and deprive it of its power.

Our feeling of empowerment was strengthened by the privilege to participate such a wonderfully provocative work of art. Provocative but not gratuitous. Provocative but not indiscriminate. Provocative but, as Alyce said, intentional. The mastery with which Mark crafted the piece captivated us and made us feel like we were a part of something meaningful. Furthermore, Mark cultivated a safe space that emphasized positivity, professionalism, and acceptance.

Reflecting on our first nude rehearsal, Cate explained, "that was the day I was like 'ok this is going to be fine,' because everybody was just very professional and very chill. It's only a big deal if you make it a big deal, and nobody was making it a big deal."

And when you think about it, it's really not that big of a deal.

Because at the end of the day we're all just bodies.

Bodies that shit and piss and sweat and fart and wrinkle and bleed and stink and creak and groan and grow hair in the worst places and lose hair in the best.

The more we strip away the more we realize how similar we all are.

And I think we could all use a little reminder of that from time to time.

Pouty Pause

With my skipping gaffe in the rearview we're soon to my favorite part of the piece, the pouty pause. On my last lap of "plastic surgery" we stop for a 4 count at the end of the stage and give the audience the look of a petulant child who was just told they couldn't have ice cream. "You're a bratty kid who didn't get their way and you want to stare at them like you're parents are the worst." I have a lot of fun with this one & really lean into it. But I REALLY want ice cream!!! Ughhhhhhhhhhhhhhh.

Photography by Ben McKeown, courtesy of the American Dance Festival.

Then comes the spear handoff. The only part I haven't rehearsed. As I reach the yellow panel I snag the spear from Cate and collect 11 rubles with a flawless pirouette that could only be described as Baryshnikovian. The quality of the pirouette is only surpassed by my immense modesty.

But it wasn't long before I goofed again, just a couple passes later during the military marching sequence. This section features a completely different walking pattern from the past half hour. I make it through the first couple laps just fine then on the third lap, for whatever reason, my brain lapses and I forget the (Nutcracker/step together/9-step/whatever name we feel like that day), which throws off my steps from my comrades. Thankfully we've rehearsed this so many dang times that I'm able to keep my composure and take a little stutter step before our skip to get back on schedule.

But since all my mental energy was focused on fixing my mistake I have completely lost my count, which puts me in a bit of a pickle since this section has a skip on the 4-count. Again, because of our extensive rehearsals, I have a pretty good feel for where the skip should go; but my ace in the hole is walking right next to me. Renay, I find, attacks the skip with an aggressiveness that could likely qualify her for the triple jump at the Olympics. I mean she really loads up for it. These forceful bounds are caught in my peripherals to confirm I'm skipping on the right count for the rest of that pass.

♥ you Renay!

Ovation

My final pass of the performance comes as the music fades out to silence. 96 steps with no soundtrack but our footsteps. I'm the very last in the line so my final lap is all alone. No music to keep my count. No compatriots to distract the audience's gaze.

Photography by Ben McKeown, courtesy of the American Dance Festival.

Seeing as this is my first performance (have I mentioned that yet?) my fellow dancers ask if I'm nervous for my solo. I have a troubling sense of calm about it. I should be nervous but for reasons I can't explain I'm not.

As I walk off the stage I don't know what to expect. I gave it a 50-50 shot that I'd get emotional backstage and tear up. But when it's all said and done the only emotion I feel is pure, unadulterated bliss. My smile spans the full distance from ear to ear.

As we're hugging backstage I realize that I might not be the only one with first show jitters. Our curtain call song, a delightful honky tonk swing ditty from Patsy, has not made its usual appearance. As we're pondering if we should just take our curtain call without music Patsy starts up. But it's not the right Patsy. It's Walkin' After Midnight, the opening song to the piece. It seems the technician in charge of the music ran into a snafu playing the song and made the tactical decision to just play the main soundtrack. We shrug and run out for the curtain call just like we practiced.

Backstage after we finish our bows McKelynn looks at me with a huge smile on her face, "oh my god they gave us a standing ovation! That doesn't happen every time!"

"Well for me it does!" I reply with a shiteating grin. I'm an ornery prick aren't I?

Are you going to the talkback?

"The what?"

"The talkback, Mark is going to talk about the piece & do a Q&A"

"Y'all have terms like adagio but the forum where a choreographer discusses their art and creative process is called a talkback?"

annoyed glares

"Yes I'm going to the talkback"

I'm just saying that even football coaches have postgame press conferences. I doubt half the coaches in the NFL could spell "conferences." A quarter probably can't spell "press."

During the talkback we learn about the story of how the piece came to be. Our current hour-long iteration was incrementally developed over time, with the original spanning a much more modest 20 minutes.

"It developed from an initial urge to play with time. The back and forth wave has a mesmerizing quality that lulls the audience into a trance before we change up the pattern and it throws them. I wanted something where the audience is just feeling bored before we change it up."

During the Q&A section my friend Sean asks Mark about his thought process behind using country music as the soundtrack for the piece.

"Honestly, before this piece I HATED country music! I couldn't stand it! But after going through and listening to hundreds of songs I have to say it grew on me and now I love country music. I was just looking for songs with good time signatures for the walking pattern and country music just seemed to work out well for that. And there's something about country music that speaks to the heart of this crazy experiment we have been living in this country"

"People think I'm teasing with the country music, criticizing America, saying that I hate this country. But I love this country, we have a lot of great things going for us, we definitely have our flaws, but there's a lot to be proud of and a lot we can work on to get better."

"Sometimes as artists we can take ourselves & our work too seriously. I'm not changing the world with this piece. I think that art can make positive changes in the world but I'm not going to think that everything that I create is going to change the world. I just wanted to make a piece that was fun and I hope that everyone had fun."

Well What Now?

I've had many friends ask why I wanted to do this. Friends who understand all the sports references I've made and none of the dance ones. Friends who wouldn't know Monica Bill Barnes if she walked in the room and did her best Monica Bill Barnes impression.

I really think it just boils down to two short words, "why not?" Seeing as the Latin for "why not" is "cur non," I reckon I have no choice but to change my stage name to Andy Curnonthoys.

All of my fellow performers are curious as to my future in the dancing arts. I've enrolled in some dance classes. I've learned what second position is. I can (kinda?) do a tendu. We're still working on my flexibility but it's been a blast. I'm open to any performances that require little to no dance experience and/or clothing. I would do this performance again in a heartbeat.

I want to thank all my fellow performers for their patience putting up with my asinine questions and inane jokes of mediocre quality:

Alexandra

Renay

Matt

Cate

Allie

Hendri

McKelynn

Carrie

Alyce

Jonathan

Brace

Dana

Linda Belans

Aaron

But most of all I want to thank Mark Haim for taking a chance on an inexperienced hayseed from Oklahoma to participate in a piece that's so meaningful to him.

When people ask me how the performance went I say the same thing every time, "it was one of the most fun experiences I've ever been a part of." From the moment I walked through the door for the audition to the moment we took our final bow it was an unrelenting torrent of joy.

A ton of work.

But a ton of fun.

And I'll never regret taking that blind pirouette into the unknown.